Enabling Shared Library Builds in Velox

In this post, I’ll share how we unblocked shared library builds in Velox, the challenges we encountered with our large CMake build system, and the creative solution that let us move forward without disrupting contributors or downstream users.

The State of the Velox Build System

Velox’s codebase was started in Meta’s internal monorepo, which still serves as a source of truth. Changes from pull requests in the Github repository are not merged directly via the web UI. Instead, the changes are imported into the internal review and CI tool Phabricator, as a ‘diff’. There, it has to pass an additional set of CI checks before being merged into the monorepo and in turn, exported to Github as a commit on the ‘main’ branch.

Internally, Meta uses the Buck2 build system which, like its predecessor Buck, promotes small, granular build targets to improve caching and distributed compilation. Externally, however, the open-source community relies on CMake as a build system. When the CMake build system was first added, its structure mirrored the granular nature of the internal build targets.

The result was hundreds of targets: over one hundred library targets, built as static libraries, and more than two hundred executables for tests and examples. While Buck(2) is optimized for managing such granular targets, the same can not be said for CMake. Each subdirectory maintained its own CMakeLists.txt, and header includes were managed through global include_directories(), with no direct link between targets and their associated header files. This approach encouraged tight coupling across module boundaries. Over the years, dependencies accumulated organically, resulting in a highly interconnected, and in parts cyclic, dependency graph.

Static Linking vs. Shared Linking

The combination of 300+ targets and static linking resulted in a massive build tree, dozens of GiB when building in release mode and several times larger when built with debug information. This grew to the point where we had to provision larger CI runners just to accommodate the build tree in debug mode!

Individual test executables could reach several GiB, making it impractical to transfer the executables between runners to parallelize the execution of the tests across different CI runners. Significantly delaying CI feedback for developers when pushing changes to a PR.

This size is the result of each static library containing a full copy of all of its dependencies' object files. With over 100+ strongly connected libraries, we end up with countless redundant copies of the same objects scattered throughout the build tree, blowing up the total size.

CMake usually requires the library dependency graph to be acyclic (a DAG). However it allows circular dependencies between static libraries, because it’s possible to adjust the linker invocation to work around possible issues with missing symbols.

For example, say library A depends on foo() from library B, and B in turn depends on bar() defined in A. If we link them in order A B, the linker will find foo() in B for use in A but will fail to find bar() for use in B. This happens because the linker processes the libraries from left to right and symbols that are not (yet) required are effectively ignored.

The trick is now simply to repeat the entire circular group in the linker arguments A B A B. Previously ignored symbols are now in the list of required symbols and can be resolved when the linker processes the repeated libraries.

However, there is no workaround for shared libraries. So the moment we attempted to build Velox as a set of shared libraries, CMake failed to configure. The textbook solution would involve refactoring dependencies between targets, explicitly marking dependencies - as PUBLIC( meaning forwarded to both direct and transitive dependents) or PRIVATE, ( required only for this target at build time), and manually breaking cycles. But with hundreds of targets and years of organic growth, this became an unmanageable task.

Solution Attempt 1: Automate

Manually addressing this was unmanageable so, our first instinct as Software Engineers was, of course, to automate the process. I wrote a python package that parses all CMakelists.txt files in the repository using Antlr4, tracks which source files and headers belong to which target and reconstructs the library dependency graph. Based on the graph and whether headers are included from a source or a header file, the tool grouped the linked targets as either PRIVATE or PUBLIC.

While this worked locally and made it easier to resolve the circular dependencies, it proved far too brittle and disruptive to implement at scale. Velox's high development velocity meant many parts of the code base changed daily, making it impossible to land modifications across over 250+ CMake files in a timely manner while also allowing for thorough review and testing. Maintaining this carefully constructed DAG of dependencies would also have required an unsustainable amount of specialized reviewer attention, time that could be spent much more productively elsewhere.

Solution: Monolithic Library via CMake Wrappers

Given the practical constraints we needed a solution that would unblock shared builds without disrupting the ongoing development. To achieve this we used a common pattern of larger CMake code bases, project specific wrapper functions. A special thanks to Marcus Hanwell for introducing me to the pattern he successfully used in VTK.

We created wrapper functions for a selection of the CMake commands that create and manage build targets: add_library became velox_add_library, target_link_libraries turned into velox_link_libraries etc. These functions just forward the arguments to the wrapped core command, unless the option to build Velox as a monolithic library is set. In the latter case instead of ~100 only a single library target is created.

Each call to velox_add_library just adds the relevant source files to the main velox target. To ensure drop-in compatibility, for every original library target, the wrapper creates an ALIAS target referring to velox. This way, all existing code, downstream consumers, old and new test targets, can continue to link to their accustomed velox_xyz targets, which effectively point to the same monolithic library. There is no need to adjust CMake files throughout the codebase, keeping the migration quick and entirely transparent to developers and users.

Some special-case libraries, such as those involving the CUDA driver, still needed to be built separately for runtime or integration reasons. The wrapper logic allows exemptions for these, letting them be built as standalone libraries even in monolithic mode.

Here's a simplified version of the relevant logic:

function(velox_add_library TARGET)

if(VELOX_MONO_LIBRARY)

if(TARGET velox)

# Target already exists, append sources to it.

target_sources(velox PRIVATE ${ARGN})

else()

add_library(velox ${ARGN})

endif()

# create alias for compatibility

add_library(${TARGET} ALIAS velox)

else()

# Just call add_library as normal

add_library(${TARGET} ${ARGN})

endif()

endfunction()

This new, monolithic library obviously doesn’t suffer from cyclic dependencies, as it only has external dependencies. So after implementing the wrapper functions, building Velox as a shared library only required some minor adjustments!

We have now switched the default configuration to build the monolithic library and transitioned to build the shared library in our main PR CI and macOS builds.

Result

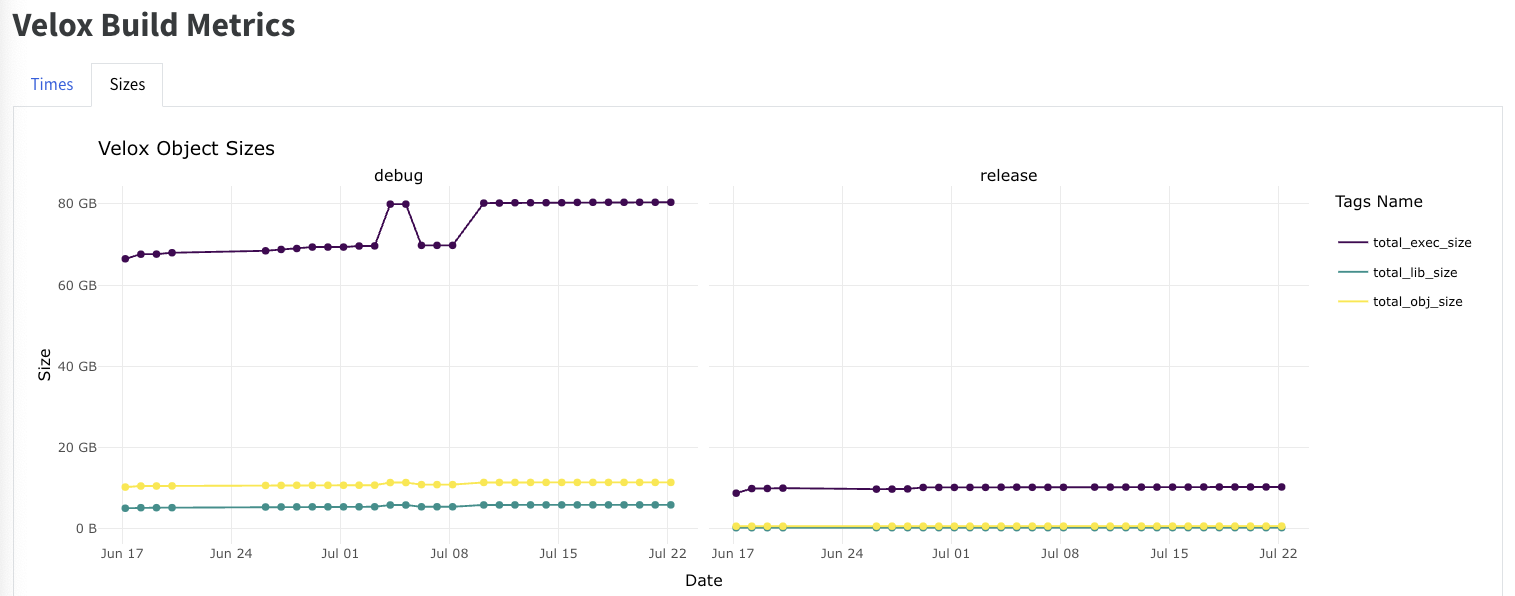

The results of our efforts can be clearly seen in our Build Metrics Report with the size of the resulting binaries being the biggest win as seen in Table 1. The workflow that collects these metrics uses our regular CI image with GCC 12.2 and ld 2.38.

The new executables built against the shared libvelox.so are a mere ~4% of their previous size! This unlocks improvements across the board both for the local developer experience, packaging/deployments for downstream users as well as CI.

| Size of executables | Static | Shared |

|---|---|---|

| Release | 18.31G | 0.76G |

| Debug | 244G | 8.8G |

Table 1: Total size of test, fuzzer and benchmark executables

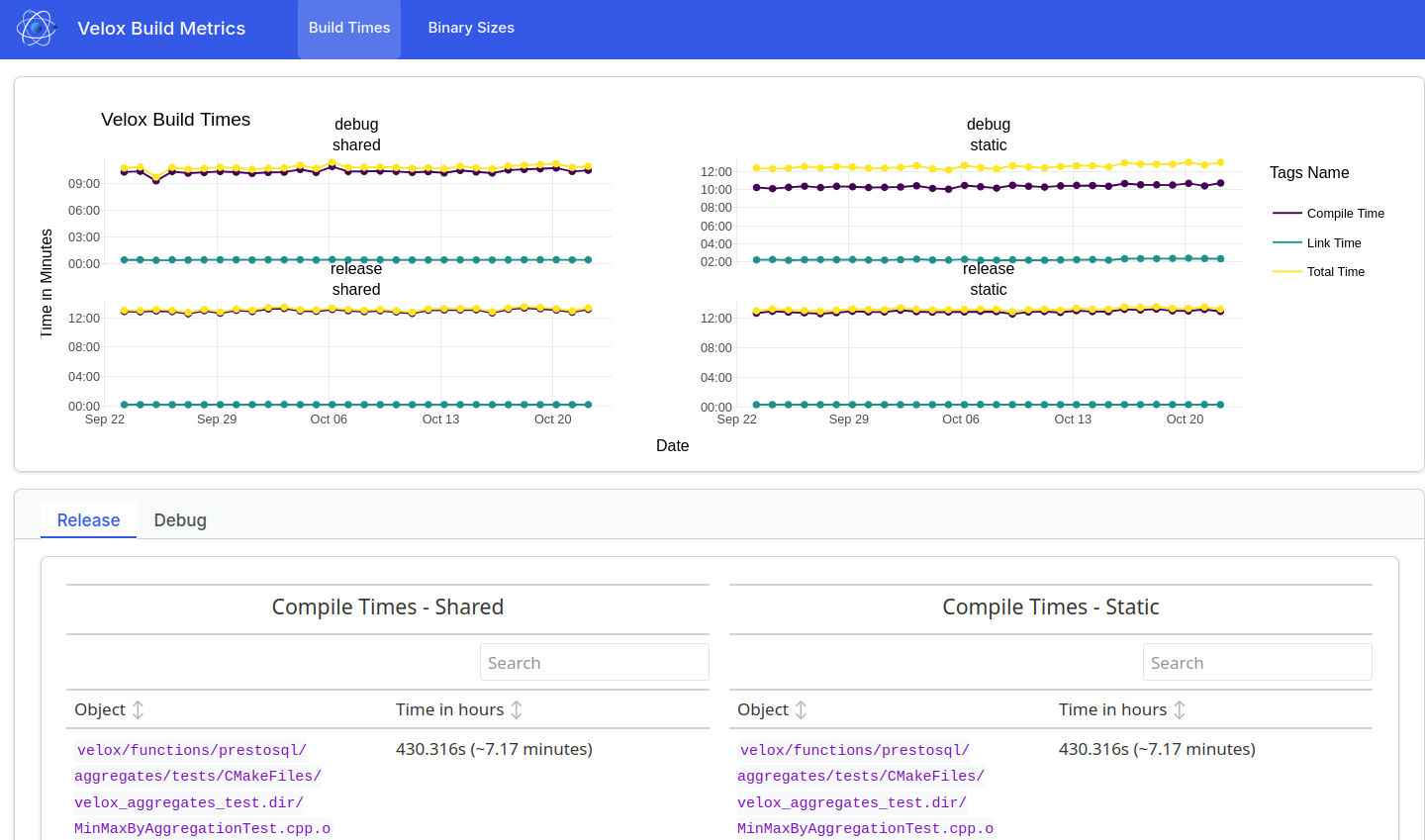

Less impressive but still notable is the reduction of the debug build time by almost two hours1. The improvement is entirely explained by the much faster link time for the shared build of ~30 minutes compared to the 2 hours and 20 minutes it takes to link the static library.

| Total CPU Time | Static | Shared |

|---|---|---|

| Release | 13:21h | 13:23h |

| Debug | 12:50h | 11:07h |

Table 2: Total time spent on compilation and linking across all cores

In addition to unblocking shared builds, the wrapper function pattern offers further benefits for future feature additions or build-system wide adjustments with minimal disruption. We already use them to automate installation of header files along the Velox libraries, with no changes to the targets themselves.

The wrapper functions will also help with defining and enforcing the public Velox API by allowing us to manage header visibility, component libraries like GPU and Cloud extensions and versioning in a consistent and centralized manner.

Footnotes

-

This is of course much less in terms of wall time the user experiences (~

CPU time/nwhere n is the number of cores used for the build) ↩